source: New York Times

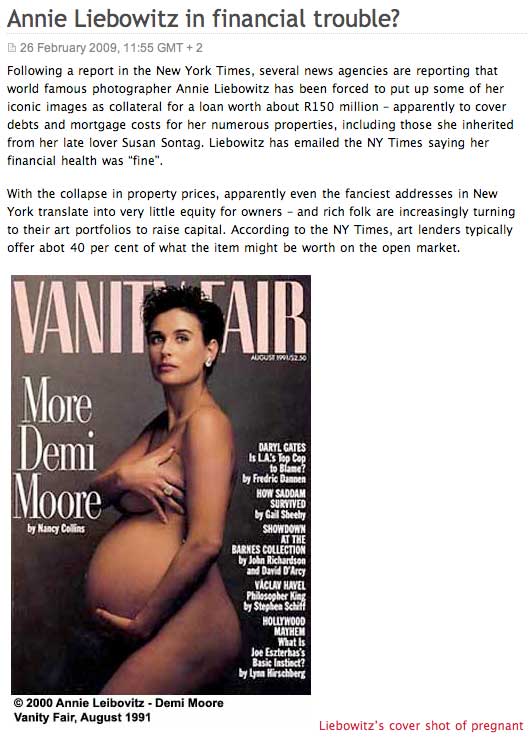

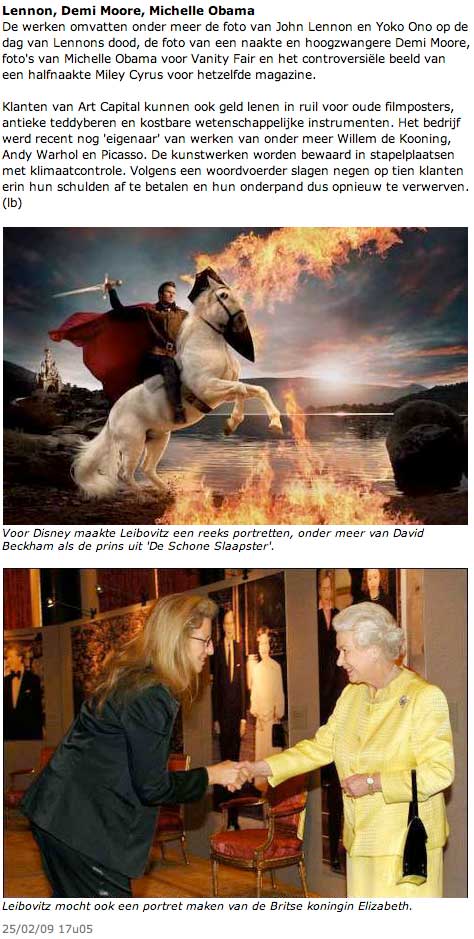

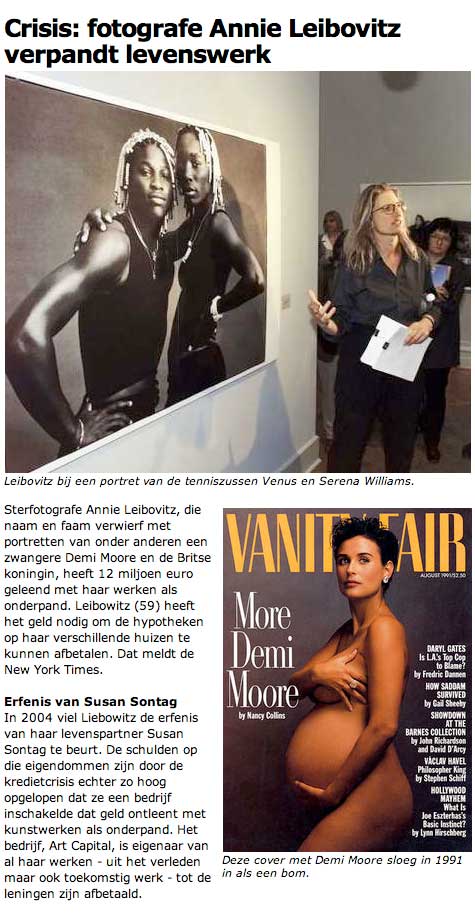

Last fall, Annie Leibovitz, the photographer, borrowed $5 million from a company called Art Capital Group. In December, she borrowed $10.5 million more from the same firm. As collateral, among other items, she used town houses she owns in Greenwich Village, a country house, and something else: the rights to all of her photographs.

In other words, according to loan documents filed with the city, one of the world's most successful photographers essentially pawned every snap of the shutter she had made or will make until the loans are paid off.

Those who know Ms. Leibovitz said she used the money to pay off mortgages and deal with other financial stresses. But whatever her reasons, she is not alone in doing business with Art Capital and similar lenders. At a time when stock portfolios are plunging and many homes, even grand ones, have no equity left to borrow against, an increasing number of art owners are realizing that an Old Master or a prime photograph, when used as collateral, can bring in much-needed cash.

"It's very discreet," said Ian Peck, a co-owner of Art Capital.

This little-known corner of the art business is lightly regulated and highly litigious. But this has not dissuaded clients who have included rich collectors like Veronica Hearst, art galleries and prominent artists themselves, including Ms. Leibovitz and Julian Schnabel.

Art Capital's headquarters in the former Sotheby's building on Madison Avenue looks at first glance like an art gallery. Two Warhols, a pair of Rubens portraits of Roman emperors and a pink nude by the contemporary Mexican painter Victor Rodriguez hang on the cool white walls. A sculpture of a faun by Rembrandt Bugatti sits on a windowsill in a conference room where transactions are discussed.

But it would be more accurate to describe the airy space as something far less genteel: a pawnshop.

Art Capital issues loans of $500,000 or more at interest rates from 6 percent to 16 percent. Fail to pay and you lose your Rubens; several of the works on display in Art Capital's office on Madison became subject to sale after their owners defaulted.

The company expects to make about $120 million in art-related loans in 2009, up from $80 million in 2008. At a Manhattan-based competitor, Art Finance Partners, "we are up 40 percent in originations in the last six months," said Meghan Carleton, a partner.

ArtLoan, a similar company in San Francisco, is actually regulated by California's pawn laws. It opened in 2004 and has seen "exponential" growth in the last year even though it charges interest rates of 18 percent to 24 percent, said Ray Parker Gaylord, an owner.

"It's a very rough-and-tumble corner of the business," said Marc Porter, who heads the American operations of Christie's auction house. Christie's and Sotheby's also offer loans against fine art but focus on bridge loans to customers who have pledged their art for planned auctions.

"For years, one of the reasons this wasn't an especially big business is that everyone was getting money for something else," Mr. Porter said. "It was easy money everywhere. But now people are looking to every asset they have to unlock cash."

ArtLoan prefers to make loans on items that are physically small and thus easy to store or to ship to auction houses and dealers in case of a default. A recent loan was for $115,000 against a collection that included an early 20th-century bronze sculpture, a 19th-century Persian carpet and a Swiss music box.

Art lenders typically lend up to 40 percent of what they appraise the artworks to be worth, and usually take possession of the works.

A former investment banker in New York, who spoke anonymously because he did not want friends to know his financial situation, is sending six modern paintings to ArtLoan, hoping to borrow $50,000 against them to finance a business venture. His former company's stock, which he was given as part of his annual bonuses, has gone from the high $70s a share to $22, he said.

1 2 3 next