Den Zustand der Welt zitierend wurden die Stichworte der letzten Krisenherde

Afganistan

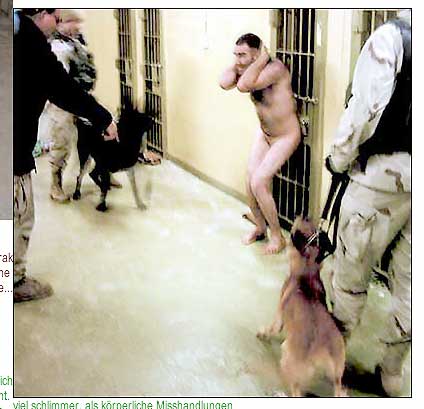

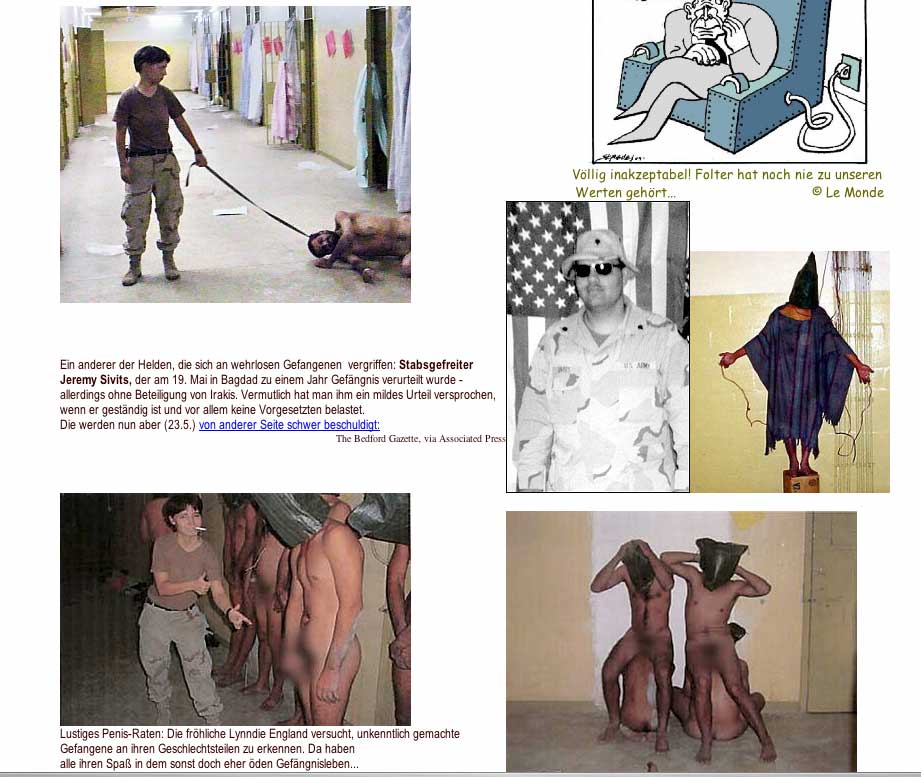

Irak

Libanon

und sonstiges unter aktuell im IN befragt

Search Books

Tools

Text-only version

Send it to a friend

Has Germany sold its post-war liberties for a mess of pottage? Sixty years

after the end of hostilities in Europe, G?nter Grass argues, global capital

has ensnared parliament, and democratic progress is in danger of becoming

a commodity to be bought and sold on the markets

Saturday May 7, 2005

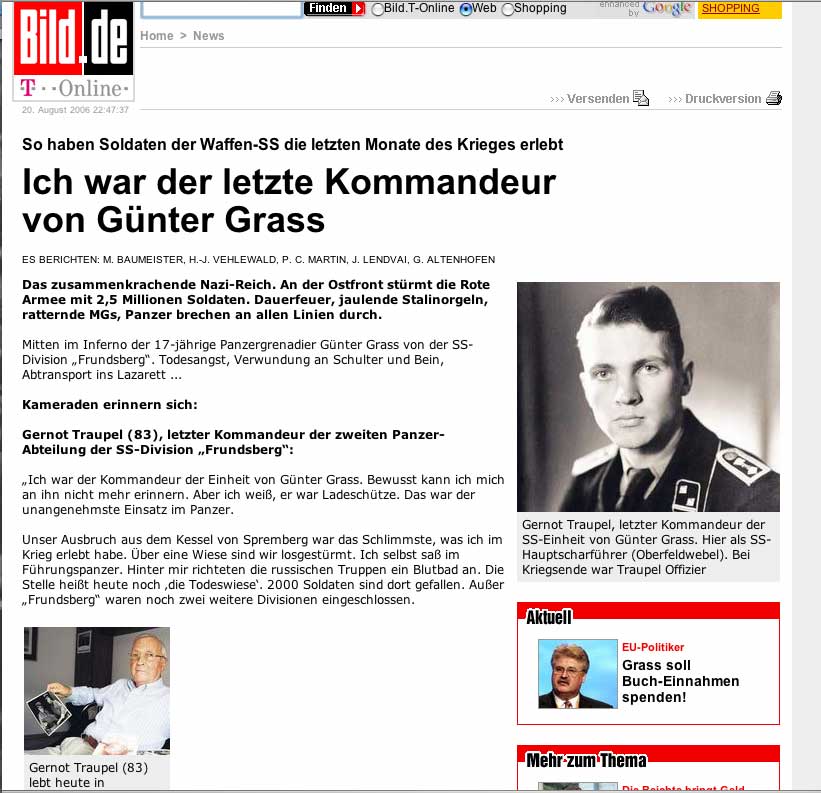

The Guardian It is 60 years since the German Reich's unconditional surrender.

That is equivalent to a working life with a pension to look forward to. So

far back that memory, that wide-meshed sieve, is in danger of forgetting

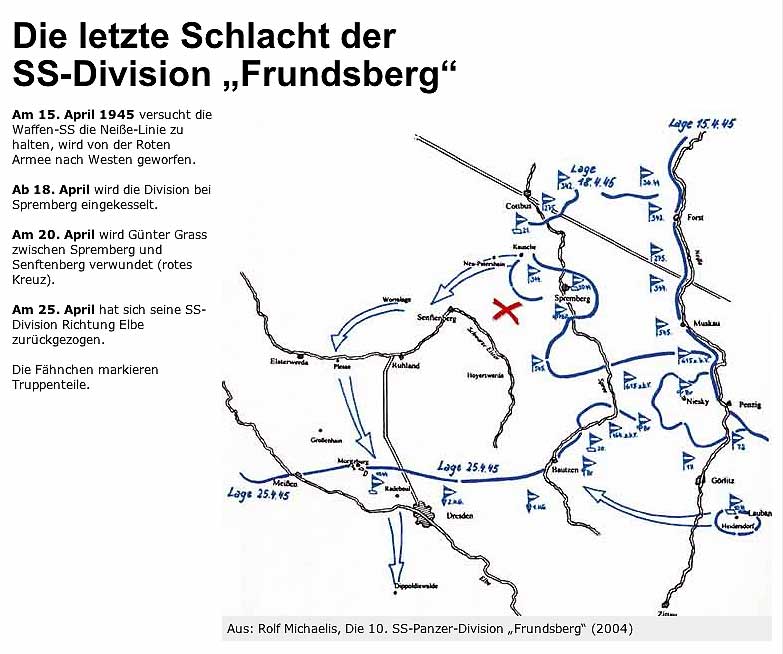

it. Sixty years ago, after being wounded in the chaotic retreat in Lausitz,

I lay

in hospital with a flesh wound in my right thigh and a bean-sized shell splinter

in my right shoulder. The hospital was in Marienbad, a military hospital

town that had been occupied by American soldiers a few days earlier, at

the same

time as Soviet forces were occupying the neighbouring town of Karlsbad. In

Marienbad, on May 8, I was a naive 17-year-old, who had believed in the ultimate

victory right to the end. Those who had survived the mass murder in the German

concentration camps could regard themselves as liberated, although they were

in no physical condition to enjoy their freedom. But for me it was not the

hour of liberation; rather, I was beset by the empty feeling of humiliation

following total defeat.

Article continues When May 8 comes round again and is celebrated in complacent

official speeches as liberation day, this can only be in hindsight, especially

as we Germans did little if anything for our liberation. In the initial post-war

years our lives were determined by hunger and cold, the misery of refugees,

the displaced and bombed-out. In all four zones occupied by the wartime allies,

Britain, France, the United States and the Soviet Union, the only way to

manage the ever-increasing crush of the more than 12 million Germans who

had fled

from, or been driven out of, East and West Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia and

the Sudentenland, was to force them into our own cramped living rooms. Whenever,

and especially in a party-political sense, the question is posed, "What

can we Germans be proud of?", the first thing we should mention is this

essential achievement — even though it was forced on us. We had hardly

got used to freedom when compulsion had to be applied. As a result, in both

German states, huge long-term camps for refugees and displaced persons were

avoided. The risk of building up feelings of hate was thereby diverted, as

was the desire for revenge engendered by years of camp life which — as

today's world shows — can result in terror and counter-terror.

So, it was an achievement of a special kind. Especially since the compulsory

settlement of refugees and displaced persons had more often than not to be

carried out in the face of xenophobic resistance from the established local

population. The realisation that all Germans, not only those bombed out and

now homeless, had lost the war dawned only hesitantly. At this early stage,

in their dealings with one another, the Germans were practising that virulent

attitude towards foreigners which still exists today.

Even then there were spokespersons for the rhetoric of liberation. They appeared

individually and in groups. So many self-appointed anti-fascists suddenly

set the tone in which one was entitled to ask: how had Hitler been able to

make

headway against such strong resistance? Dirty linen was quickly washed clean,

with people being absolved of all responsibility. Counterfeiters were subsequently

busy coining new expressions and putting them into circulation. Unconditional

surrender was changed to "collapse". Although in business, law and

in the rapidly re-emerging schools and universities, even the diplomatic service,

many former National Socialists maintained their hereditary wealth, stayed

in office, continued to hold on to their university chairs and eventually continued

their careers in politics, it was claimed that we were starting from "zero

hour" or square one. A particularly infamous distortion of facts can be

seen even today in speeches and publications, with the crimes perpetrated by

Germans described as "misdeeds perpetrated in the name of the German people".

In addition, language was used in two different ways to herald the future

division of the country. In the Soviet occupied zone, the Red Army had liberated

Germany

from the fascist terror all by itself; in the Western occupied zones, the

honour of having freed not only Germany but the whole of Europe from Nazi

domination

was shared exclusively by the Americans, the British and the French.

In the Cold War that quickly followed, German states which had existed since

1949 consistently fell to one or other power bloc, whereupon the governments

of both national entities sought to present themselves as model pupils of

their respective dominating powers. Forty years later, during the Glasnost

period

it was ironically the Soviet Union that broke up the Democratic Republic,

which had by that point become a burden. The Federal Republic's almost unconditional

subservience to the US was broken for the first time when the SPD-Green ruling

coalition decided to make use of the freedom given to us in sovereign terms

60 years ago, by refusing to allow German soldiers to participate in the

Iraq

war.

"

Donated Freedom" was the title of a speech which I gave to the Berlin

Academy of Arts on May 8 1985. At the time, the country was still divided,

so I compared both states, their need for disassociation, their different dependencies,

their own particular brand of dogmatic materialism, their fear of and their

longing for unification. The "Donated Freedom" applied only to

the West German state, the Eastern one went away empty-handed.

Twenty years later, in view of the condition of the Federal Republic, now

enlarged through reunification, we question how this gift was used. Have

we dealt carefully

with the freedom which we did not win, but was given to us? Have the citizens

of West Germany properly compensated the citizens of the former Democratic

republic who, after all, had to bear the main burden of the war begun and

lost by all Germans? And a further question: is our parliamentary democracy

as a

guarantor of freedom of action, still sufficiently sovereign to take action

on the problems facing us in the 21st century?

Fifteen years after signing the Treaty of Unity, we can no longer conceal

or gloss over the fact that, despite the financial achievements, German unity

has essentially been a failure. And was right from the start. Petty calculation

prevented the government of the time from pursuing an objective grounded

in

the Constitutional Act by way of precaution, namely to submit to the citizens

of both states a new constitution relevant to the endeavours of Germany as

a whole. It is therefore hardly surprising that people in the former East

Germany should regard themselves as second-class Germans. As far as the ownership

of

manufacturing establishments, the energy supply, newspapers and publishing

are concerned, this formerly "nationally owned" fabric of the departed

state has been wound up with the occasionally criminal collusion of the privatisation

agency and ultimately expropriated. The jobless rate is twice as high as in

the former West Germany. West German arrogance had no respect for people with

East German cv's. The formerly feared migration of the population — which

led to the over-hasty introduction of the West German Deutschmark into East

Germany — is happening now, daily. Whole areas of the country, its

cities and its villages, are being emptied. After the privatisation agency

had completed

its bargain sales, West German industry and similarly the banks withheld

the necessary investment and loans and, consequently, no jobs were created.

Here,

fine exhortations are of little use. In view of this skewed situation, only

parliament, the lawmakers, can help. Which brings us back to the question

of whether parliamentary democracy is able to act.

Now, I believe that our freely elected members of parliament are no longer

free to decide. The customary party pressures, for which there may well be

reasons, are not critical here; it is, rather, the ring of lobbyists with

their multifarious interests that constricts and influences the Federal parliament

and its democratically elected members, placing them under pressure and forcing

them into disharmony, even when framing and deciding the content of laws.

Favours

minor and major smooth the way. Reprehensible scams are dismissed as sorry

misdemeanours. No one any longer takes serious exception to what is now a

sophisticated system, operating on the basis of reciprocal backhanders.

Consequently, parliament is no longer sovereign in its decisions. It depends

on powerful pressure groups — the banks and multinationals — which

are not subject to any democratic control. Parliament has thereby become an

object of ridicule. It is degenerating into a subsidiary of the stock exchange.

Democracy has become a pawn to the dictates of globally volatile capital. So

can we really be surprised when more and more citizens turn away from such

blatant scams, indignant, an tagonised and ultimately resigned and regard elections

as a simple farce and decline to vote? What is needed is a democratic desire

to protect Parliament against the pressures of the lobbyists by making it inviolable.

But are our parliamentarians still sufficiently free for a decision that would

bring radical democratic constraint? Once again the question arises, what has

become of the freedom presented to us sixty years ago? Is it now no more than

a stock market profit? Our highest constitutional value no longer protects

civil rights as a priority, and has rather been wasted at cut prices, so that

it now only serves the so-called free-market economy in line with the neoliberal

Zeitgeist. Yet this concept, which has become a fetish, barely conceals the

asocial conduct of the banks, industrial associations and market speculators.

We all are witnesses to the fact that production is being destroyed worldwide,

that so-called hostile and friendly takeovers are destroying thousands of jobs,

that the mere announcement of rationalisation measures, such as the dismissal

of workers and employees, makes share prices rise, and this is regarded unthinkingly

as the price to be paid for "living in freedom".

The consequences of this development disguised as globalisation are clearly

coming to light and can be read from the statistics. With the consistently

high number of jobless, which in Germany has now reached five million, and

the equally constant refusal of industry to create new jobs, despite demonstrably

higher earnings, especially in the export area, the hope of full employment

has evaporated. Older employees, who still had years of work left in them,

are pushed into early retirement. Young people are denied the skills for

entering the world of work. Even worse, with simultaneous complaints that

an ageing

population is a threat and the demand, repeated parrot-fashion, to do more

for young people and education, the Federal Republic — still a rich country — is

permitting, to a shameful extent, the growth of what is called "child

poverty".

All this is now accepted as if divinely ordained, accompanied at most by

the customary national grumbles. Questions as to responsibility are sent

straight

to the shunting department. Here, they are shunted first to one siding, then

then to the other. Yet the future of more than a million children growing

up in impoverished families remains in the balance. Those who point to this

state

of affairs and to the people forced into social oblivion are at best ridiculed

by slick young journalists as "social romantics", but usually vilified

as "Do-gooders". Questions asked as to the reasons for the growing

gap between rich and poor are dismissed as "the politics of envy".

The desire for justice is ridiculed as utopian. The concept of "solidarity" is

relegated to the dictionary's list of "foreign words".

Here the rich farmer and well-fed, there the nameless who seek refuge in

the soup kitchen. Here the cool better-off - there the statistically-recorded

social

problem cases. In the Federal Republic of Germany the classless society,

regarded by all as highly desirable, is changing into a class-based society

that was

long thought to be outdated. No longer a possibility but a hard fact: what

is paraded as neo-liberal proves to be on close scrutiny a return to disparaging

practices of early capitalism. And the social market economy - formerly a

successful model of economic and cohesive action - has degenerated into the

free market

economy for which the constitutional obligation of employers to contribute

to workers' pensions is an irritation and the striving for profit is sacrosanct.

When we were given freedom 60 years ago and, defeated, initially did not

know what to do with it, we gradually made use of this gift. We learned democracy

and in doing so proved star pupils — because after all we were incontrovertibly

German. With the benefit of hindsight, what was crammed into us through lectures

was enough to get us a reasonable end-of-term report. We learned the interplay

between government and opposition, whereupon lengthy periods of government

ultimately proved arid. The much lauded and reviled generation of '68 produced

new people and ultimately also tolerance. We had to acknowledge that our

burdens could not be cast aside, they are passed by parents to children and

our German

past, however much we travel and export, comes back to haunt us. Neo-Nazis

repeatedly brought us into disrepute. Even so, we felt that democracy was

here to stay. It had to withstand several challenges. Another is upon us.

After the debris had been cleared and disposed of in both German states,

reconstruction in the East proceeded under the constraints of the Stalinist

system; but in

the Western state, it took place under favourable conditions. What retrospectively

is called the "economic miracle" was not, however, due to any individual

achievement, but was won by many. Included in that number are displaced persons

and refugees, those who had in fact to start at square one in terms of material

possessions. We must not forget the contribution of foreign workers, initially

politely called "guest workers". In the rebuilding phase businessmen

were exemplary in investing every penny of profit into job creation. The

trades unions and businesses were clearly aware of the decay of the Weimar

Republic,

so they were forced to compromise and ensure social equality. However, with

so much toil and profit-chasing, the past was in danger of being forgotten.

Only in the sixties were questions asked, firstly by writers then by a youth

movement, simply called "student protest", about everything that

the older people, the war generation, would sooner forget. The protest movement

strove verbally for revolution, but was paid off with reform, for which,

often unintentionally, it had created the climate. But for it, we would still

be

living in the claustrophobic fog of the Adenauer years. Without the youth

movement, the social-liberal coalition's new Germany policy, as a gradual

convergence

of the two states, could not have been achieved.

The third challenge arose when the Wall had fallen and, on a larger scale,

the division of Europe ended, at least in terms of power politics. The two

German states had existed for four decades more against than beside each

other. As there was no willingness on the Western side to offer the East

equal rights,

the unity of the country has so far existed only on paper. It was all done

too hastily and without an understanding of what far-reaching consequences

this haste would have.

Since then, the expanded country has stagnated. Neither the Kohl government

nor the Schröder government has succeeded in correcting the initial errors.

Lately, perhaps too late, we have come to recognise that the threat to the

state — or what should be regarded as Public Enemy No 1 — comes

not from right-wing radicalism but rather, from the impotence of politics,

which leaves citizens exposed and unprotected from the dictates of the economy.

Workers and employees are increasingly blackmailed by the corporate group.

Not parliament but the pharmaceutical industry and the doctors' and chemists'

associations dependent on it decide who must profit and reap the benefit

of health reform. Instead of the social obligation which derives from owning

property,

maximising profits has become the basic principle. Freely elected MPs submit

to both the domestic and global pressure of high finance. So what is being

destroyed is not the state, which survives, but democracy.

When the German Reich unconditionally surrendered 60 years ago, a system

of power and terror was thereby defeated. This system, which had caused fear

throughout

Europe for 12 years, still leaves its shadow today. We Germans have repeatedly

faced up to this inherited shame and have been forced to do so if we hesitated.

The memory of the suffering that we caused others and ourselves has been

kept alive through the generations. We often had to force ourselves to face

this.

Compared with other nations which have to live with shame acquired elsewhere — I'm

thinking of Japan, Turkey, the former European colonial powers — we

have not shaken off the burden of our past. It will remain part of our history

as

an ongoing challenge. We can only hope we will be able to cope with today's

risk of a new totalitarianism, backed as it is by the world's last remaining

ideology.

As conscious democrats, we should freely resist the power of capital, which

sees mankind as nothing more than something which consumes and produces.

Those who treat their donated freedom as a stock market profit have failed

to understand

what May 8 teaches us every year.

Special report

Germany

Guardian Unlimited © Guardian Newspapers Limited 2006